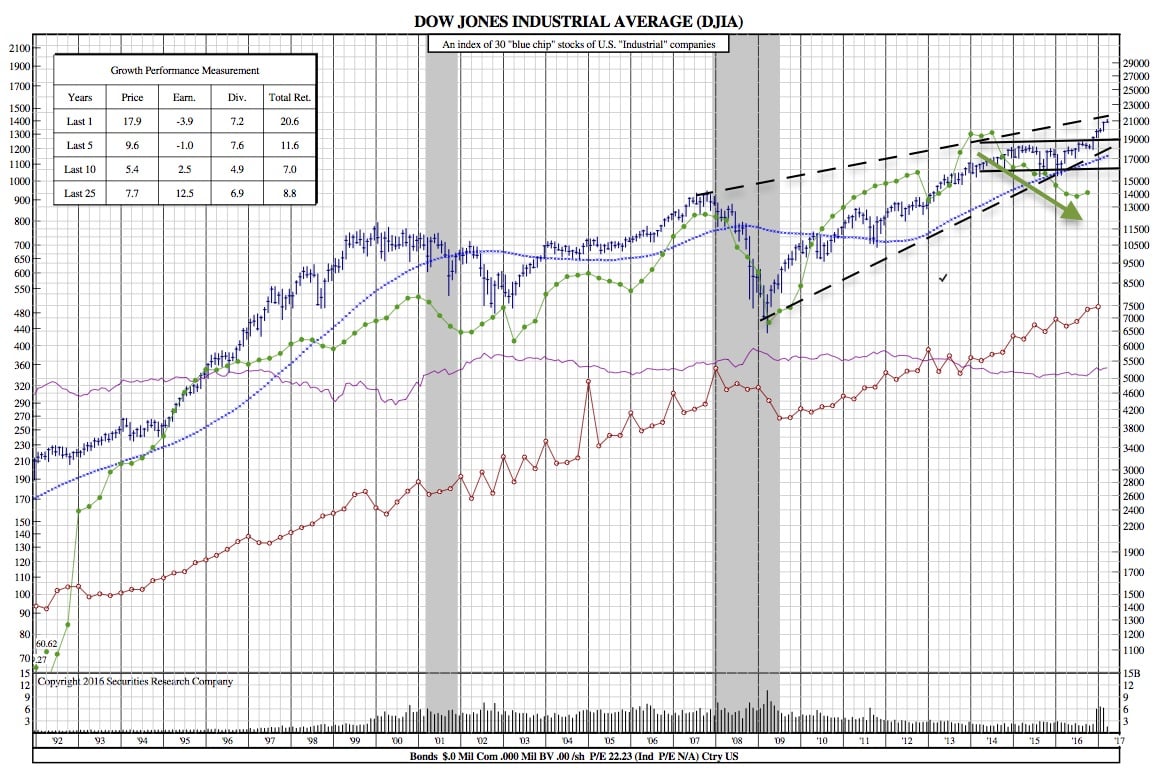

Is the Market in a State of Euphoria and is it Signaling a Looming Bear Market? (DJIA 35-Year Chart)

Wall Street Journal — Bull markets are born on pessimism, grow on skepticism, mature on optimism and die on euphoria—Sir John Templeton

Eight years ago today, investors were more pessimistic than they had been in many decades. Stocks had crashed back to where they stood almost 13 years earlier, banks were failing and comparisons to the Great Depression of the 1930s were routine. It was a great time to buy.

Fast forward to 2017 and the S&P 500 has stormed up 254% from the March 2009 low, money is pouring into shares, confidence is high and stocks expensive. On the model used by legendary British investor Sir John Templeton, the aging bull market is definitely sustained by optimism, and perhaps already becoming euphoric.

Also Read: SRC – The S&P 500 hasn’t done this since 1994 (35-Year Chart)

For investors, this creates a dilemma: chase the returns a final blowout would bring, or switch to cash now to survive the bear market that might follow?

The decision depends on the assessment of the risks and rewards of chasing a shift to euphoria. Bank of America Merrill Lynch recently upgraded its forecast for the S&P 500 at the end of this year to 2450, after the index powered through its previous prediction of 2300. Strategist Dan Suzuki said that valuations look high, but noted the upgrade was driven by increasing investor optimism.

“It’s euphoria taking hold,” Mr. Suzuki says. “We’re in the cautious camp [on valuations]. We’re just trying to recognize that that’s not what drives markets.” Looking back over the past 80 years of market cycles, the minimum blowout in the final two years was 30%, with many bull markets ending in a much bigger splurge before the bust eventually arrived.

Put another way: The market’s not really worth more, but exuberant buyers will chase shares higher anyway. As veteran strategist Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research puts it, to make money from here “you’re not making it as an investor, you’re making it as a speculator.”

The reason for caution is the high valuation of every dollar of earnings, even as profit margins are high compared with history and companies have a lot of leverage. A return to historically lower margins or valuations would hurt while adding debt becomes harder the more companies have.

Still, valuations have been higher, notably in the 2000 bubble, when they went to levels never seen before on every widely used measure. There’s little sign of dot-com-era excesses—Snap’s IPO pop excepted—but the period has become the standard comparison for today’s valuations.

Doug Ramsey, chief investment officer of the Leuthold Group in Minneapolis, reckons there could be gains of 36% to more than 100% depending on the valuation tool used if dot-com peak levels were reached again (although he doesn’t expect that).

But today’s market is very different than the late 1990s when gains were concentrated in big telecoms, media and technology stocks. Today pretty much everything is expensive, and the valuation of the median stock is much closer to where it was at the turn of the century. Indeed, Mr. Ramsey calculates that even with what he calls an “outlandish and probably irresponsible” assumption that median valuations rise to match-dot-com levels, the S&P 500would rise less than 12%.

He’s still invested in stocks, expecting that gains will become more concentrated in popular stocks and sectors as the bull market ages, as happened in past cycles back to the 1920s. “Before the next major bear market you should have signs of internal deterioration in the market,” he says.

Not everyone is so confident that they can predict either the boom or the bust. Value investors are finding fewer opportunities and holding more cash.

The flagship Benchmark-Free Allocation fund of GMO in Boston is more than a fifth in cash. “Largely that’s for lack of something else to buy right now,” says Catherine LeGraw, a member of the asset allocation team.

Explaining to clients that it’s worth missing out on a possible boom in order to buy more cheaply in the subsequent bust is hard. “Newer clients have a little bit of hand-wringing of ‘why do you have so much cash, why am I paying you for so much cash,’” says Ms. LeGraw. Some have left.

Investors faced with the dilemma of whether to buy an already-expensive market in the hope that it gets even more expensive should examine their own motivations. Shifting to cash looks appealing, but if the market goes up another 20% from here, will you change your mind and buy back in? Another 30%? If so, better to stay invested now than buy in even closer to the top. Value investing works in the long run, but only for those able to stay unruffled as their friends get rich in the final euphoria of bull markets.

DJIA 25-Year Chart: